Application Fundamentals

An Android package, which is an archive file with an .apk suffix, contains the contents of an Android app that are required at runtime and it is the file that Android-powered devices use to install the app.

An Android App Bundle, which is an archive file with an .aab suffix, contains the contents of an Android app project including some additional metadata that is not required at runtime. An AAB is a publishing format and is not installable on Android devices, it defers APK generation and signing to a later stage. When distributing your app through Google Play for example, Google Play’s servers generate optimized APKs that contain only the resources and code that are required by a particular device that is requesting installation of the app.

Each Android app lives in its own security sandbox, protected by the following Android security features:

- The Android operating system is a multi-user Linux system in which each app is a different user.

- By default, the system assigns each app a unique Linux user ID (the ID is used only by the system and is unknown to the app). The system sets permissions for all the files in an app so that only the user ID assigned to that app can access them.

- Each process has its own virtual machine (VM), so an app’s code runs in isolation from other apps.

- By default, every app runs in its own Linux process. The Android system starts the process when any of the app’s components need to be executed, and then shuts down the process when it’s no longer needed or when the system must recover memory for other apps.

App components

App components are the essential building blocks of an Android app. Each component is an entry point through which the system or a user can enter your app. Some components depend on others.

There are four different types of app components:

- Activities

- Services

- Broadcast receivers

- Content providers

Each type serves a distinct purpose and has a distinct lifecycle that defines how the component is created and destroyed.

App Architecture

An app architecture defines the boundaries between parts of the app and the responsibilities each part should have. In order to meet the needs mentioned above, you should design your app architecture to follow a few specific principles.

Principles

Separation of concerns

The most important principle to follow is separation of concerns.

Drive UI from data models

Another important principle is that you should drive your UI from data models, preferably persistent models.

Single source of truth

When a new data type is defined in your app, you should assign a Single Source of Truth (SSOT) to it.

The single source of truth principle is often used in our guides with the Unidirectional Data Flow (UDF) pattern. In UDF, state flows in only one direction. The events that modify the data flow in the opposite direction.

Recommended app architecture

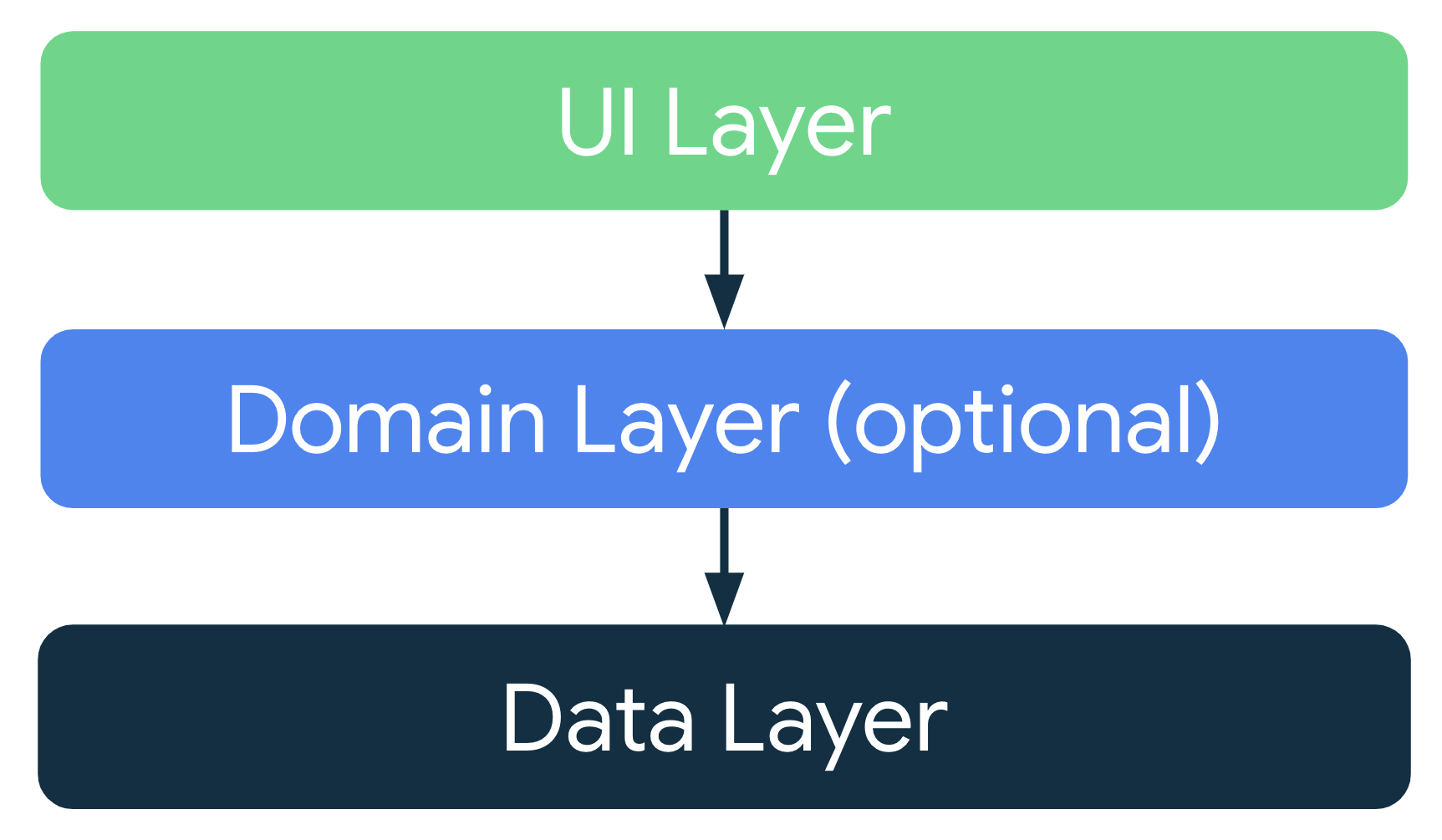

Considering the common architectural principles mentioned in the previous section, each application should have at least two layers:

- The UI layer that displays application data on the screen.

- The data layer that contains the business logic of your app and exposes application data.

You can add an additional layer called the domain layer to simplify and reuse the interactions between the UI and data layers.

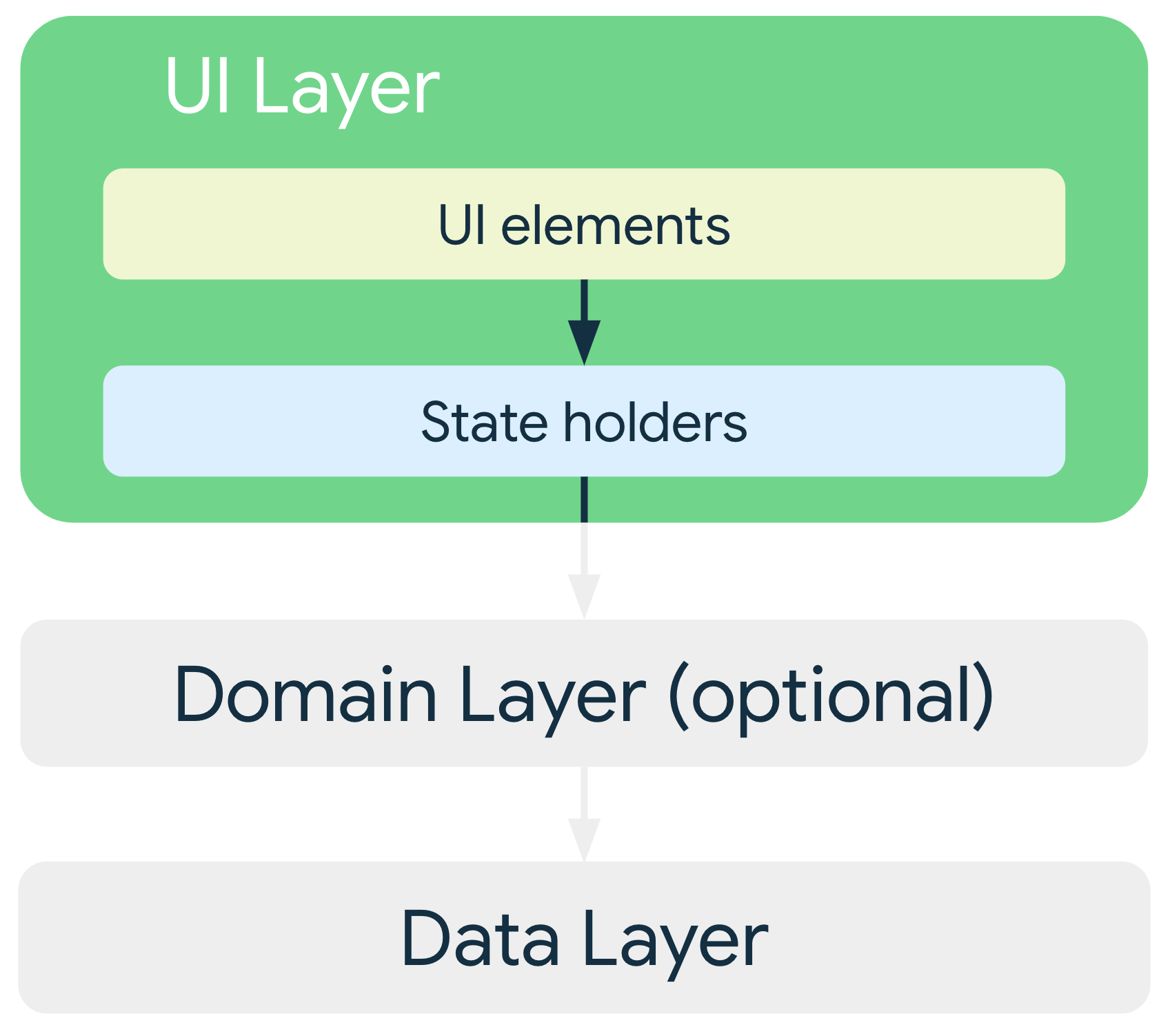

UI layer

The role of the UI layer (or presentation layer) is to display the application data on the screen. Whenever the data changes, either due to user interaction (such as pressing a button) or external input (such as a network response), the UI should update to reflect the changes.

The UI layer is made up of two things:

- UI elements that render the data on the screen. You build these elements using Views or Jetpack Compose functions.

- State holders (such as ViewModel classes) that hold data, expose it to the UI, and handle logic.

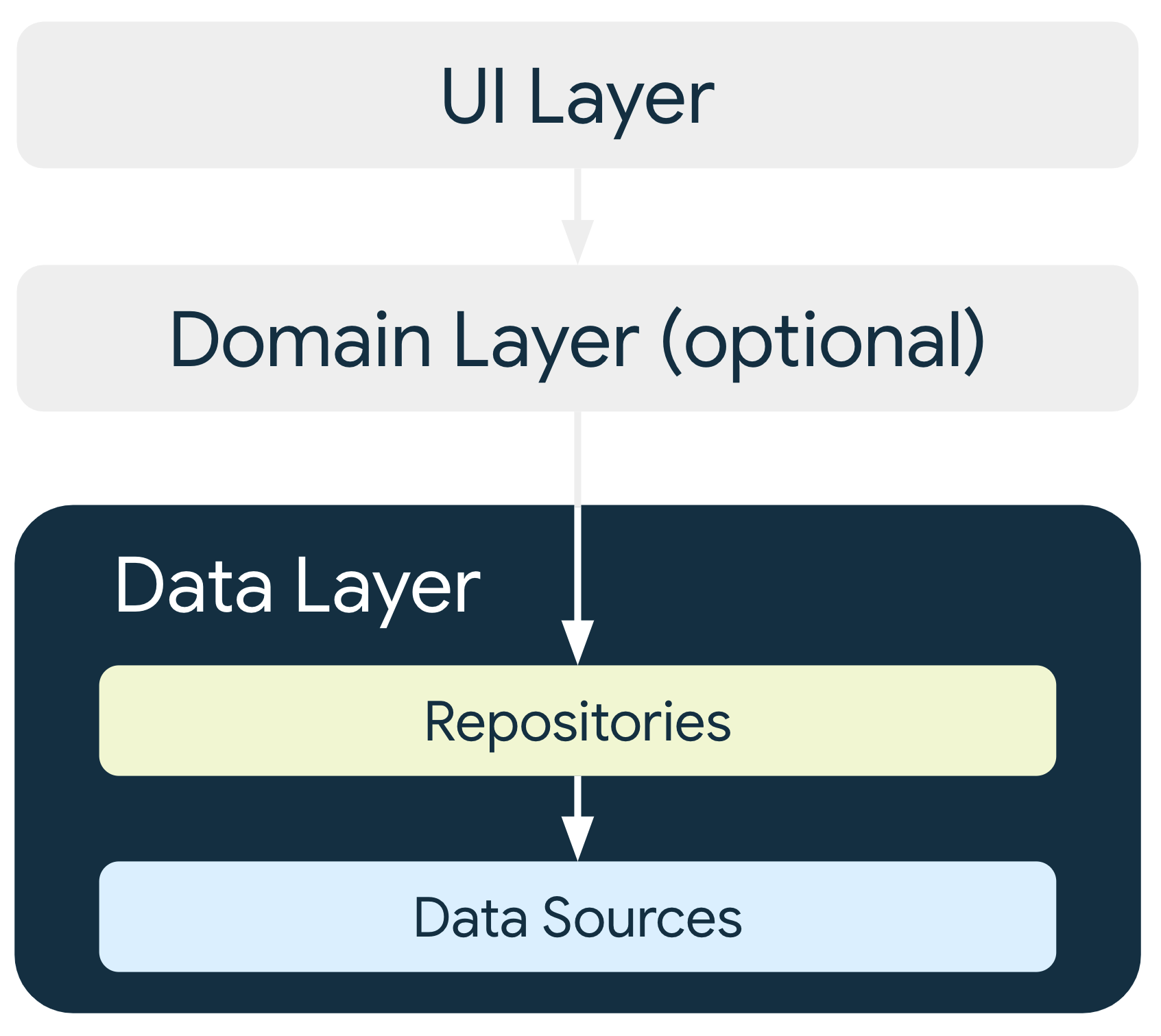

Data layer

The data layer of an app contains the business logic. The business logic is what gives value to your app—it’s made of rules that determine how your app creates, stores, and changes data.

The data layer is made of repositories that each can contain zero to many data sources. You should create a repository class for each different type of data you handle in your app.

Repository classes are responsible for the following tasks:

- Exposing data to the rest of the app.

- Centralizing changes to the data.

- Resolving conflicts between multiple data sources.

- Abstracting sources of data from the rest of the app.

- Containing business logic.

Each data source class should have the responsibility of working with only one source of data, which can be a file, a network source, or a local database. Data source classes are the bridge between the application and the system for data operations.

Domain layer

The domain layer is an optional layer that sits between the UI and data layers.

The domain layer is responsible for encapsulating complex business logic, or simple business logic that is reused by multiple ViewModels. This layer is optional because not all apps will have these requirements. You should use it only when needed—for example, to handle complexity or favor reusability.

Classes in this layer are commonly called use cases or interactors. Each use case should have responsibility over a single functionality. For example, your app could have a GetTimeZoneUseCase class if multiple ViewModels rely on time zones to display the proper message on the screen.

General best practices

Don’t store data in app components.

Avoid designating your app’s entry points—such as activities, services, and broadcast receivers—as sources of data.

Reduce dependencies on Android classes.

Your app components should be the only classes that rely on Android framework SDK APIs such as

Context, orToast.Create well-defined boundaries of responsibility between various modules in your app.

For example, don’t spread the code that loads data from the network across multiple classes or packages in your code base. Similarly, don’t define multiple unrelated responsibilities—such as data caching and data binding—in the same class.

Expose as little as possible from each module.

Focus on the unique core of your app so it stands out from other apps.

Don’t reinvent the wheel by writing the same boilerplate code again and again.

Consider how to make each part of your app testable in isolation.

Types are responsible for their concurrency policy.

If a type is performing long-running blocking work, it should be responsible for moving that computation to the right thread.

Persist as much relevant and fresh data as possible.

That way, users can enjoy your app’s functionality even when their device is in offline mode.

State

There are three ways to declare a MutableState object in a composable:

val value = remember { mutableStateOf(default) }var value by remember { mutableStateOf(default) }val (value, setValue) = remember { mutableStateOf(default) }

These declarations are equivalent, and are provided as syntax sugar for different uses of state

Caution: Using mutable objects such as

ArrayList<T>ormutableListOf()as state in Compose causes your users to see incorrect or stale data in your app. Mutable objects that are not observable, such as ArrayList or a mutable data class, are not observable by Compose and don’t trigger a recomposition when they change. Instead of using non-observable mutable objects, the recommendation is to use an observable data holder such asState<List<T>>and the immutablelistOf().

While remember helps you retain state across recompositions, the state is not retained across configuration changes. For this, you must use rememberSaveable. rememberSaveable automatically saves any value that can be saved in a Bundle.

Compose automatically recomposes from reading

Stateobjects. If you use another observable type such asLiveDatain Compose, you should convert it toStatebefore reading it. Make sure that type conversion happens in a composable, using a composable extension function likeLiveData<T>.observeAsState().

State hoisting

State hoisting in Compose is a pattern of moving state to a composable’s caller to make a composable stateless.

The general pattern for state hoisting in Jetpack Compose is to replace the state variable with two parameters:

value: T: the current value to displayonValueChange: (T) -> Unit: an event that requests the value to change, whereTis the proposed new value

UI state

UI state is the property that describes the UI. There are two types of UI state:

- Screen UI state is what you need to display on the screen. This state is usually connected with other layers of the hierarchy because it contains app data.

- UI element state refers to properties intrinsic to UI elements that influence how they are rendered. A UI element may be shown or hidden and may have a certain font, font size, or font color.

Logic

Logic in an application can be either business logic or UI logic:

- Business logic is the implementation of product requirements for app data. For example, bookmarking an article in a news reader app when the user taps the button. This logic to save a bookmark to a file or database is usually placed in the domain or data layers. The state holder usually delegates this logic to those layers by calling the methods they expose.

- UI logic is related to how to display UI state on the screen. For example, obtaining the right search bar hint when the user has selected a category, scrolling to a particular item in a list, or the navigation logic to a particular screen when the user clicks a button.

UI Logic

When UI logic needs to read or write state, you should scope the state to the UI, following its lifecycle. To achieve this, you should hoist the state at the correct level in a composable function. Alternatively, you can do so in a plain state holder class, also scoped to the UI lifecycle.

Key Point: Keeping UI element state internal to composable functions is acceptable. This is a good solution if the state and logic you apply to it is simple and other parts of the UI hierarchy don’t need the state.

Business logic

If composables and plain state holders classes are in charge of the UI logic and UI element state, a screen level state holder is in charge of the following tasks:

- Providing access to the business logic of the application that is usually placed in other layers of the hierarchy such as the business and data layers.

- Preparing the application data for presentation in a particular screen, which becomes the screen UI state.

The benefits of AAC ViewModels in Android development make them suitable for providing access to the business logic and preparing the application data for presentation on the screen.

When you hoist UI state in the ViewModel, you move it outside of the Composition.

Figure 6: State hoisted to the ViewModel is stored outside of the Composition.

ViewModels aren’t stored as part of the Composition. They’re provided by the framework and they’re scoped to a ViewModelStoreOwner which can be an Activity, Fragment, navigation graph, or destination of a navigation graph.

You should inject the ViewModel instance in your screen-level composables to provide access to business logic.

Note: You should not pass

ViewModelinstances down to other composables.

ConversationScreen

ConversationScreen

unidirectional data flow

The pattern where the state goes down, and events go up is called a unidirectional data flow.

Key Point: When hoisting state, there are three rules to help you figure out where state should go:

- State should be hoisted to at least the lowest common parent of all composables that use the state (read).

- State should be hoisted to at least the highest level it may be changed (write).

- If two states change in response to the same events they should be hoisted together.

You can hoist state higher than these rules require, but underhoisting state makes it difficult or impossible to follow unidirectional data flow.

state storage

Parcelize

The simplest solution is to add the @Parcelize annotation to the object. The object becomes parcelable, and can be bundled. For example, this code makes a parcelable City data type and saves it to the state.

@Parcelize

data class City(val name: String, val country: String) : Parcelable

@Composable

fun CityScreen() {

var selectedCity = rememberSaveable {

mutableStateOf(City("Madrid", "Spain"))

}

}

MapSaver

If for some reason @Parcelize is not suitable, you can use mapSaver to define your own rule for converting an object into a set of values that the system can save to the Bundle.

data class City(val name: String, val country: String)

val CitySaver = run {

val nameKey = "Name"

val countryKey = "Country"

mapSaver(

save = { mapOf(nameKey to it.name, countryKey to it.country) },

restore = { City(it[nameKey] as String, it[countryKey] as String) }

)

}

@Composable

fun CityScreen() {

var selectedCity = rememberSaveable(stateSaver = CitySaver) {

mutableStateOf(City("Madrid", "Spain"))

}

}

ListSaver

To avoid needing to define the keys for the map, you can also use listSaver and use its indices as keys:

data class City(val name: String, val country: String)

val CitySaver = listSaver<City, Any>(

save = { listOf(it.name, it.country) },

restore = { City(it[0] as String, it[1] as String) }

)

@Composable

fun CityScreen() {

var selectedCity = rememberSaveable(stateSaver = CitySaver) {

mutableStateOf(City("Madrid", "Spain"))

}

}

Lifecycle

The lifecycle of a composable is defined by the following events:

- entering the Composition

- getting recomposed 0 or more times

- leaving the Composition.

Recomposition is typically triggered by a change to a State object. Compose tracks these and runs all composables in the Composition that read that particular State<T>, and any composables that they call that cannot be skipped.

A Composable’s’ lifecycle is simpler than the lifecycle of views, activities, and fragments. When a composable needs to manage or interact with external resources that do have a more complex lifecycle, you should use effects.

Add extra information to help smart recompositions

@Composable

fun MoviesScreen(movies: List<Movie>) {

Column {

for (movie in movies) {

key(movie.id) { // Unique ID for this movie

MovieOverview(movie)

}

}

}

}

Stable

If a composable is already in the Composition, it can skip recomposition if all the inputs are stable and haven’t changed.

A stable type must comply with the following contract:

- The result of

equalsfor two instances will forever be the same for the same two instances. - If a public property of the type changes, Composition will be notified.

- All public property types are also stable.

There are some important common types that fall into this contract that the compose compiler will treat as stable, even though they are not explicitly marked as stable by using the @Stable annotation:

- All primitive value types:

Boolean,Int,Long,Float,Char, etc. - Strings

- All Function types (lambdas)

All of these types are able to follow the contract of stable because they are immutable. Since immutable types never change, they never have to notify Composition of the change, so it is much easier to follow this contract.

Note: All deeply immutable types can safely be considered stable types.

One notable type that is stable but is mutable is Compose’s MutableState type. If a value is held in a MutableState, the state object overall is considered to be stable as Compose will be notified of any changes to the .value property of State.

If Compose is not able to infer that a type is stable, but you want to force Compose to treat it as stable, mark it with the @Stable annotation.

Modifiers

odifiers allow you to decorate or augment a composable. Modifiers let you do these sorts of things:

- Change the composable’s size, layout, behavior, and appearance

- Add information, like accessibility labels

- Process user input

- Add high-level interactions, like making an element clickable, scrollable, draggable, or zoomable

It’s a best practice to have all of your Composables accept a modifier parameter, and pass that modifier to its first child that emits UI.

The order of modifier functions is significant. Since each function makes changes to the Modifierreturned by the previous function, the sequence affects the final result.

Multiple modifiers can be chained together to decorate or augment a composable. This chain is created via the Modifier interface which represents an ordered, immutable list of single Modifier.Elements.

Each Modifier.Element represents an individual behavior, like layout, drawing and graphics behaviors, all gesture-related, focus and semantics behaviors, as well as device input events. Their ordering matters: modifier elements that are added first will be applied first.

Sometimes it can be beneficial to reuse the same modifier chain instances in multiple composables, by extracting them into variables and hoisting them into higher scopes. It can improve code readability or help improve your app’s performance.

val reusableModifier = Modifier

.fillMaxWidth()

.background(Color.Red)

.padding(12.dp)

You can further chain or append your extracted modifier chains by calling the .then() function:

val reusableModifier = Modifier

.fillMaxWidth()

.background(Color.Red)

.padding(12.dp)

// Append to your reusableModifier

reusableModifier.clickable { … }

// Append your reusableModifier

otherModifier.then(reusableModifier)

Side-effects

A side-effect is a change to the state of the app that happens outside the scope of a composable function.

Composables should be side-effect free. When you need to make changes to the state of the app, you should use the Effect APIs so that those side effects are executed in a predictable manner.

Key Term: An effect is a composable function that doesn’t emit UI and causes side effects to run when a composition completes.

LaunchedEffect: run suspend functions in the scope of a composable

To call suspend functions safely from inside a composable, use the LaunchedEffect composable. When LaunchedEffect enters the Composition, it launches a coroutine with the block of code passed as a parameter. The coroutine will be cancelled if LaunchedEffect leaves the composition. If LaunchedEffect is recomposed with different keys, the existing coroutine will be cancelled and the new suspend function will be launched in a new coroutine.

@Composable

fun LandingScreen(onTimeout: () -> Unit) {

// This will always refer to the latest onTimeout function that

// LandingScreen was recomposed with

val currentOnTimeout by rememberUpdatedState(onTimeout)

// Create an effect that matches the lifecycle of LandingScreen.

// If LandingScreen recomposes, the delay shouldn't start again.

LaunchedEffect(true) {

delay(SplashWaitTimeMillis)

currentOnTimeout()

}

/* Landing screen content */

}

rememberCoroutineScope: obtain a composition-aware scope to launch a coroutine outside a composable

As LaunchedEffect is a composable function, it can only be used inside other composable functions. In order to launch a coroutine outside of a composable, but scoped so that it will be automatically canceled once it leaves the composition, use rememberCoroutineScope

rememberCoroutineScope is a composable function that returns a CoroutineScope bound to the point of the Composition where it’s called. The scope will be cancelled when the call leaves the Composition.

@Composable

fun LandingScreen(onTimeout: () -> Unit) {

// This will always refer to the latest onTimeout function that

// LandingScreen was recomposed with

val currentOnTimeout by rememberUpdatedState(onTimeout)

// Create an effect that matches the lifecycle of LandingScreen.

// If LandingScreen recomposes, the delay shouldn't start again.

LaunchedEffect(true) {

delay(SplashWaitTimeMillis)

currentOnTimeout()

}

/* Landing screen content */

}

rememberUpdatedState: reference a value in an effect that shouldn’t restart if the value changes

LaunchedEffect restarts when one of the key parameters changes. However, in some situations you might want to capture a value in your effect that, if it changes, you do not want the effect to restart. In order to do this, it is required to use rememberUpdatedState to create a reference to this value which can be captured and updated. This approach is helpful for effects that contain long-lived operations that may be expensive or prohibitive to recreate and restart.

For example, suppose your app has a LandingScreen that disappears after some time. Even if LandingScreen is recomposed, the effect that waits for some time and notifies that the time passed shouldn’t be restarted:

@Composable

fun LandingScreen(onTimeout: () -> Unit) {

// This will always refer to the latest onTimeout function that

// LandingScreen was recomposed with

val currentOnTimeout by rememberUpdatedState(onTimeout)

// Create an effect that matches the lifecycle of LandingScreen.

// If LandingScreen recomposes, the delay shouldn't start again.

LaunchedEffect(true) {

delay(SplashWaitTimeMillis)

currentOnTimeout()

}

/* Landing screen content */

}

DisposableEffect: effects that require cleanup

For side effects that need to be cleaned up after the keys change or if the composable leaves the Composition, use DisposableEffect. If the DisposableEffect keys change, the composable needs to dispose (do the cleanup for) its current effect, and reset by calling the effect again.

@Composable

fun HomeScreen(

lifecycleOwner: LifecycleOwner = LocalLifecycleOwner.current,

onStart: () -> Unit, // Send the 'started' analytics event

onStop: () -> Unit // Send the 'stopped' analytics event

) {

// Safely update the current lambdas when a new one is provided

val currentOnStart by rememberUpdatedState(onStart)

val currentOnStop by rememberUpdatedState(onStop)

// If `lifecycleOwner` changes, dispose and reset the effect

DisposableEffect(lifecycleOwner) {

// Create an observer that triggers our remembered callbacks

// for sending analytics events

val observer = LifecycleEventObserver { _, event ->

if (event == Lifecycle.Event.ON_START) {

currentOnStart()

} else if (event == Lifecycle.Event.ON_STOP) {

currentOnStop()

}

}

// Add the observer to the lifecycle

lifecycleOwner.lifecycle.addObserver(observer)

// When the effect leaves the Composition, remove the observer

onDispose {

lifecycleOwner.lifecycle.removeObserver(observer)

}

}

/* Home screen content */

}

SideEffect: publish Compose state to non-compose code

To share Compose state with objects not managed by compose, use the SideEffect composable, as it’s invoked on every successful recomposition.

@Composable

fun rememberAnalytics(user: User): FirebaseAnalytics {

val analytics: FirebaseAnalytics = remember {

/* ... */

}

// On every successful composition, update FirebaseAnalytics with

// the userType from the current User, ensuring that future analytics

// events have this metadata attached

SideEffect {

analytics.setUserProperty("userType", user.userType)

}

return analytics

}

produceState: convert non-Compose state into Compose state

produceState launches a coroutine scoped to the Composition that can push values into a returned State. Use it to convert non-Compose state into Compose state, for example bringing external subscription-driven state such as Flow, LiveData, or RxJava into the Composition.

The producer is launched when produceState enters the Composition, and will be cancelled when it leaves the Composition.

@Composable

fun loadNetworkImage(

url: String,

imageRepository: ImageRepository

): State<Result<Image>> {

// Creates a State<T> with Result.Loading as initial value

// If either `url` or `imageRepository` changes, the running producer

// will cancel and will be re-launched with the new inputs.

return produceState<Result<Image>>(initialValue = Result.Loading, url, imageRepository) {

// In a coroutine, can make suspend calls

val image = imageRepository.load(url)

// Update State with either an Error or Success result.

// This will trigger a recomposition where this State is read

value = if (image == null) {

Result.Error

} else {

Result.Success(image)

}

}

}

Note: Composables with a return type should be named the way you’d name a normal Kotlin function, starting with a lowercase letter.

derivedStateOf: convert one or multiple state objects into another state

Use derivedStateOf when a certain state is calculated or derived from other state objects. Using this function guarantees that the calculation will only occur whenever one of the states used in the calculation changes.

@Composable

fun TodoList(highPriorityKeywords: List<String> = listOf("Review", "Unblock", "Compose")) {

val todoTasks = remember { mutableStateListOf<String>() }

// Calculate high priority tasks only when the todoTasks or highPriorityKeywords

// change, not on every recomposition

val highPriorityTasks by remember(highPriorityKeywords) {

derivedStateOf { todoTasks.filter { it.containsWord(highPriorityKeywords) } }

}

Box(Modifier.fillMaxSize()) {

LazyColumn {

items(highPriorityTasks) { /* ... */ }

items(todoTasks) { /* ... */ }

}

/* Rest of the UI where users can add elements to the list */

}

}

snapshotFlow: convert Compose’s State into Flows

Use snapshotFlow to convert State objects into a cold Flow. snapshotFlow runs its block when collected and emits the result of the State objects read in it. When one of the State objects read inside the snapshotFlow block mutates, the Flow will emit the new value to its collector if the new value is not equal to the previous emitted value (this behavior is similar to that of Flow.distinctUntilChanged).

The following example shows a side effect that records when the user scrolls past the first item in a list to analytics:

val listState = rememberLazyListState()

LazyColumn(state = listState) {

// ...

}

LaunchedEffect(listState) {

snapshotFlow { listState.firstVisibleItemIndex }

.map { index -> index > 0 }

.distinctUntilChanged()

.filter { it == true }

.collect {

MyAnalyticsService.sendScrolledPastFirstItemEvent()

}

}

Restarting effects

As a rule of thumb, mutable and immutable variables used in the effect block of code should be added as parameters to the effect composable. Apart from those, more parameters can be added to force restarting the effect. If the change of a variable shouldn’t cause the effect to restart, the variable should be wrapped in rememberUpdatedState. If the variable never changes because it’s wrapped in a remember with no keys, you don’t need to pass the variable as a key to the effect.

You can use a constant like true as an effect key to make it follow the lifecycle of the call site.

Phases

Like most other UI toolkits, Compose renders a frame through several distinct phases.

Compose has three main phases:

- Composition: What UI to show. Compose runs composable functions and creates a description of your UI.

- Layout: Where to place UI. This phase consists of two steps: measurement and placement. Layout elements measure and place themselves and any child elements in 2D coordinates, for each node in the layout tree.

- Drawing: How it renders. UI elements draw into a Canvas, usually a device screen.

The order of these phases is generally the same, allowing data to flow in one direction from composition to layout to drawing to produce a frame (also known as unidirectional data flow). BoxWithConstraints and LazyColumn and LazyRow are notable exceptions, where the composition of its children depends on the parent’s layout phase.

Architectural Layering

The major layers of Jetpack Compose are:

Each layer is built upon the lower levels, combining functionality to create higher level components.

Semantics

The Composition is a tree-structure that consists of the composables that describe your UI.

Next to the Composition, there exists a parallel tree, called the Semantics tree. This tree describes your UI in an alternative manner that is understandable for Accessibility services and for the Testing framework.

If your app consists of composables and modifiers from the Compose foundation and material library, the Semantics tree is automatically filled and generated for you. However when you’re adding custom low-level composables, you will have to manually provide its semantics

CompositionLocal

CompositionLocals can be used as an implicit way to have data flow through a composition.

CompositionLocal elements are usually provided with a value in a certain node of the UI tree. That value can be used by its composable descendants without declaring the CompositionLocal as a parameter in the composable function.

// Define a CompositionLocal global object with a default

// This instance can be accessed by all composables in the app

val ActiveUser = compositionLocalOf<User> { error("No active user found!") }

@Composable

fun UserPhoto() {

val user = ActiveUser.current

ProfileIcon(src = user.profilePhotoUrl)

}

@Composable

fun App(user: User) {

CompositionLocalProvider(ActiveUser provides user) {

SomeScreen()

}

}

@Composable

fun SomeScreen() {

UserPhoto()

}

@Composable

fun UserPhoto() {

val user = ActiveUser.current

ProfileIcon(src = user.profilePhotoUrl)

}

There are two APIs to create a CompositionLocal:

compositionLocalOf: Changing the value provided during recomposition invalidates only the content that reads itscurrentvalue.staticCompositionLocalOf: UnlikecompositionLocalOf, reads of astaticCompositionLocalOfare not tracked by Compose. Changing the value causes the entirety of thecontentlambda where theCompositionLocalis provided to be recomposed, instead of just the places where thecurrentvalue is read in the Composition.

If the value provided to the CompositionLocal is highly unlikely to change or will never change, use staticCompositionLocalOf to get performance benefits.

Navigation

The NavController is the central API for the Navigation component. It is stateful and keeps track of the back stack of composables that make up the screens in your app and the state of each screen.

You can create a NavController by using the rememberNavController() method in your composable:

val navController = rememberNavController()

You should create the NavController in the place in your composable hierarchy where all composables that need to reference it have access to it. This follows the principles of state hoisting and allows you to use the NavController and the state it provides via currentBackStackEntryAsState() to be used as the source of truth for updating composables outside of your screens.

Each NavController must be associated with a single NavHost composable. The NavHost links the NavController with a navigation graph that specifies the composable destinations that you should be able to navigate between. As you navigate between composables, the content of the NavHost is automatically recomposed. Each composable destination in your navigation graph is associated with a route.

Key Term: Route is a

Stringthat defines the path to your composable. You can think of it as an implicit deep link that leads to a specific destination. Each destination should have a unique route.

Creating the NavHost requires the NavController previously created via rememberNavController() and the route of the starting destination of your graph. NavHost creation uses the lambda syntax from the Navigation Kotlin DSL to construct your navigation graph. You can add to your navigation structure by using the composable() method. This method requires that you provide a route and the composable that should be linked to the destination:

NavHost(navController = navController, startDestination = "profile") {

composable("profile") { Profile(/*...*/) }

composable("friendslist") { FriendsList(/*...*/) }

/*...*/

}

Note: the Navigation Component requires that you follow the Principles of Navigation and use a fixed starting destination. You should not use a composable value for the

startDestinationroute.

To navigate to a composable destination in the navigation graph, you must use the navigate method. navigate takes a single String parameter that represents the destination’s route. To navigate from a composable within the navigation graph, call navigate:

navController.navigate("friendslist")

By default, navigate adds your new destination to the back stack. You can modify the behavior of navigate by attaching additional navigation options to our navigate() call:

// Pop everything up to the "home" destination off the back stack before

// navigating to the "friendslist" destination

navController.navigate("friendslist") {

popUpTo("home")

}

// Pop everything up to and including the "home" destination off

// the back stack before navigating to the "friendslist" destination

navController.navigate("friendslist") {

popUpTo("home") { inclusive = true }

}

// Navigate to the "search” destination only if we’re not already on

// the "search" destination, avoiding multiple copies on the top of the

// back stack

navController.navigate("search") {

launchSingleTop = true

}

Destinations can be grouped into a nested graph to modularize a particular flow in your app’s UI. An example of this could be a self-contained login flow.

The nested graph encapsulates its destinations. As with the root graph, a nested graph must have a destination identified as the start destination by its route. This is the destination that is navigated to when you navigate to the route associated with the nested graph.

To add a nested graph to your NavHost, you can use the navigation extension function:

NavHost(navController, startDestination = "home") {

...

// Navigating to the graph via its route ('login') automatically

// navigates to the graph's start destination - 'username'

// therefore encapsulating the graph's internal routing logic

navigation(startDestination = "username", route = "login") {

composable("username") { ... }

composable("password") { ... }

composable("registration") { ... }

}

...

}

It is strongly recommended that you split your navigation graph into multiple methods as the graph grows in size. This also allows multiple modules to contribute their own navigation graphs.

fun NavGraphBuilder.loginGraph(navController: NavController) {

navigation(startDestination = "username", route = "login") {

composable("username") { ... }

composable("password") { ... }

composable("registration") { ... }

}

}

By making the method an extension method on NavGraphBuilder, you can use it alongside the prebuilt navigation, composable, and dialog extension methods:

NavHost(navController, startDestination = "home") {

...

loginGraph(navController)

...

}

UI Design

Layout

Column

Use

Columnto place items vertically on the screen.Row

Similarly, use

Rowto place items horizontally on the screen. BothColumnandRowsupport configuring the alignment of the elements they contain.Box

Use

Boxto put elements on top of another.Boxalso supports configuring specific alignment of the elements it contains.

Often these building blocks are all you need. You can write your own composable function to combine these layouts into a more elaborate layout that suits your app.

To set children’s position within a Row, set the horizontalArrangement and verticalAlignment arguments. For a Column, set the verticalArrangement and horizontalAlignment arguments.

In order to know the constraints coming from the parent and design the layout accordingly, you can use a BoxWithConstraints.

Content slots

Material Components that support inner content (text labels, icons, etc.) tend to offer “slots” — generic lambdas that accept composable content — as well as public constants, like size and padding, to support laying out inner content to match Material specifications.

Testing APIs

There are three main ways to interact with elements:

- Finders let you select one or multiple elements (or nodes in the Semantics tree) to make assertions or perform actions on them.

- Assertions are used to verify that the elements exist or have certain attributes.

- Actions inject simulated user events on the elements, such as clicks or other gestures.

Some of these APIs accept a SemanticsMatcher to refer to one or more nodes in the semantics tree.

Finders

You can use onNode and onAllNodes to select one or multiple nodes respectively, but you can also use convenience finders for the most common searches, such as onNodeWithText , onNodeWithContentDescription, etc.

composeTestRule

.onNode(hasText("Button")) // Equivalent to onNodeWithText("Button")

Assertions

Check assertions by calling assert() on the SemanticsNodeInteraction returned by a finder with one or multiple matchers:

// Single matcher:

composeTestRule

.onNode(matcher)

.assert(hasText("Button")) // hasText is a SemanticsMatcher

// Multiple matchers can use and / or

composeTestRule

.onNode(matcher).assert(hasText("Button") or hasText("Button2"))

You can also use convenience functions for the most common assertions, such as assertExists , assertIsDisplayed , assertTextEquals , etc. You can browse the complete list in the Compose Testing cheat sheet.

Actions

To inject an action on a node, call a perform…() function:

composeTestRule.onNode(...).performClick()

Note: You cannot chain actions inside a perform function. Instead, make multiple

perform()calls.