Introduction

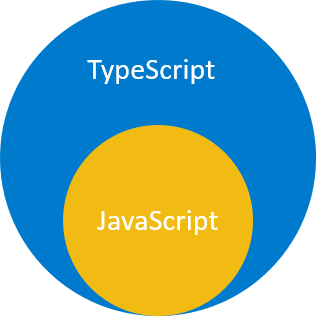

TypeScript is Typed JavaScript. TypeScript adds types to JavaScript to help you speed up the development by catching errors before you even run the JavaScript code.

TypeScript is a super set of JavaScript.

There are two main reasons to use TypeScript:

- TypeScript adds a type system to help you avoid many problems with dynamic types in JavaScript.

- TypeScript implements the future features of JavaScript a.k.a ES Next so that you can use them today.

Type

In TypeScript, a type is a convenient way to refer to the different properties and functions that a value has.

A value is anything that you can assign to a variable e.g., a number, a string, an array, an object, and a function.

In TypeScript:

- a type is a label that describes the different properties and method that a value has

- every value has a type.

TypeScript inherits the built-in types from JavaScript. TypeScript types is categorized into:

- Primitive types

The following illustrates the primitive types in TypeScript:

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

string | represents text data |

number | represents numeric values |

boolean | has true and false values |

null | has one value: null |

undefined | has one value: undefined. It is a default value of an uninitialized variable |

symbol | represents a unique constant value |

- Object types

Objec types are functions, arrays, classes, etc. Later, you’ll learn how to create custom object types.

detail

number

All numbers in TypeScript are either floating-point values that get the number type or big integers that get the

biginttype.let hexadecimal: number = 0XA; let big: bigint = 9007199254740991n;string

In TypeScript, all strings get the

stringtype. Like JavaScript, TypeScript uses double quotes ("), single quotes ('), and backtick (`) to surround string literals.Object and object

The

objecttype represents all non-primitive values while theObjecttype describes the functionality of all objects.empty type {}

TypeScript has another type called empty type denoted by

{}, which is quite similar to the object type.The empty type

{}describes an object that has no property on its own. If you try to access a property on such object, TypeScript will issue a compile-time errorTuple

A tuple works like an array with some additional considerations:

- The number of elements in the tuple is fixed.

- The types of elements are known, and need not be the same.

Since TypeScript 3.0, a tuple can have optional elements specified using the question mark (?) postfix.

let bgColor, headerColor: [number, number, number, number?]; bgColor = [0, 255, 255, 0.5]; headerColor = [0, 255, 255];Enum

An enum is a group of named constant values. Enum stands for enumerated type.

To define an enum, you follow these steps:

- First, use the

enumkeyword followed by the name of the enum. - Then, define constant values for the enum.

enum name {constant1, constant2, ...};An enum member is both a number and a defined constant.

TypeScript defines the numeric value of an enum’s member based on the order of that member that appears in the enum definition.

It’s possible to explicitly specify numbers for the members of an enum:

enum Month { Jan = 1, Feb, Mar, Apr, May, Jun, Jul, Aug, Sep, Oct, Nov, Dec };You should use an enum when you:

- Have a small set of fixed values that are closely related

- And these values are known at compile time.

- First, use the

any

The

anytype allows you to assign a value of any type to a variable.The

anytype provides you with a way to work with existing JavaScript codebase. It allows you to gradually opt-in and opt-out of type checking during compilation. Therefore, you can use theanytype for migrating a JavaScript project over to TypeScript.If you declare a variable without specifying a type, TypeScript assumes that you use the

anytype. This feature is called type inference. Basically, TypeScript guesses the type of the variable.Note that to disable implicit typing to the

anytype, you change thenoImplicitAnyoption in thetsconfig.jsonfile to b.If you declare a variable with the

objecttype, you can also assign it any value.However, you cannot call a method on it even the method actually exists.

void

The

voidtype denotes the absence of having any type at all. It is a little like the opposite of theanytype.Typically, you use the

voidtype as the return type of functions that do not return a value.function log(message): void { console.log(messsage); }It is a good practice to add the

voidtype as the return type of a function or a method that doesn’t return any value. By doing this, you can gain the following benefits:- Improve clarity of the code: you do not have to read the whole function body to see if it returns anything.

- Ensure type-safe: you will never assign the function with the

voidreturn type to a variable.

Notice that if you use the

voidtype for a variable, you can only assignundefinedto that variable. In this case, thevoidtype is not useful.never

The

nevertype is a type that contains no values. Because of this, you cannot assign any value to a variable with anevertype.Typically, you use the

nevertype to represent the return type of a function that always throws an error.function raiseError(message: string): never { throw new Error(message); }Variables can also acquire the

nevertype when you narrow its type by a type guard that can never be true.For example, without the

nevertype, the following function causes an error because not all code paths return a value.function fn(a: string | number): boolean { if (typeof a === "string") { return true; } else if (typeof a === "number") { return false; } }To make the code valid, you can return a function whose return type is the

nevertype.function fn(a: string | number): boolean { if (typeof a === "string") { return true; } else if (typeof a === "number") { return false; } // make the function valid return neverOccur(); } let neverOccur = () => { throw new Error('Never!'); }union

The union type allows you to combine multiple types into one type.

let result: number | string; result = 10; // OK result = 'Hi'; // also OK result = false; // a boolean value, not OKfunction

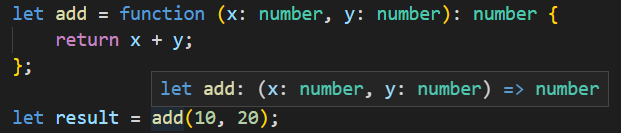

A function type has two parts: parameters and return type. When declaring a function type, you need to specify both parts with the following syntax:

(parameter: type, parameter:type,...) => typeOnce annotating a variable with a function type, you can assign the function with the same type to the variable.

If a function has different branches that return different types, the TypeScript compiler may infer the

uniontype oranytype.Therefore, it is important to add type annotations to a function as much as possible.

TypeScript compiler can figure out the function type when you have the type on one side of the equation. This form of type inference is called contextual typing.

String Literal Type

The string literal types allow you to define a type that accepts only one specified string literal.

let click: 'click';The string literal type is useful to limit a possible string value in a variable.

The string literal types can combine nicely with the union types to define a finite set of string literal values for a variable:

let mouseEvent: 'click' | 'dblclick' | 'mouseup' | 'mousedown'; mouseEvent = 'click'; // valid mouseEvent = 'dblclick'; // valid mouseEvent = 'mouseup'; // valid mouseEvent = 'mousedown'; // valid mouseEvent = 'mouseover'; // compiler errorIf you use the string literal types in multiple places, they will be very verbose.

To avoid this, you can use the type aliases.

type MouseEvent: 'click' | 'dblclick' | 'mouseup' | 'mousedown'; let mouseEvent: MouseEvent; mouseEvent = 'click'; // valid mouseEvent = 'dblclick'; // valid mouseEvent = 'mouseup'; // valid mouseEvent = 'mousedown'; // valid mouseEvent = 'mouseover'; // compiler error let anotherEvent: MouseEvent;

Type Annotation

TypeScript uses type annotations to explicitly specify types for identifiers such variables, functions, objects, etc.

TypeScript uses the syntax : type after an identifier as the type annotation, where type can be any valid type.

let variableName: type;

let variableName: type = value;

const constantName: type = value;

//array

let arrayName: type[];

//object

let person: {

name: string;

age: number

};

let employee: object;

//functions

let greeting : (name: string) => string;

Type Inference

Type inference describes where and how TypeScript infers types when you don’t explicitly annotate them. Type inference occurs when you initialize variables, set parameter default values, and determine function return types. TypeScript uses the best common type algorithm to select the best candidate types that are compatible with all variables. TypeScript also uses contextual typing to infer types of variables based on the locations of the variables.

In practice, you should always use the type inference as much as possible. And you use the type annotation in the folowing cases:

- When you declare a variable and assign it a value later.

- When you want a variable that can’t be inferred.

- When a function returns the

anytype and you need to clarify the value.

Type Aliases

Type aliases allow you to create a new name for an existing type. The following shows the syntax of the type alias:

type alias = existingType;

type chars= string;

The existing type can be any valid TypeScript type.

It’s useful to create type aliases for union types.

Type Gaurd

Type Guards allow you to narrow down the type of a variable within a conditional block.

- typeof

type alphanumeric = string | number;

function add(a: alphanumeric, b: alphanumeric) {

if (typeof a === 'number' && typeof b === 'number') {

return a + b;

}

if (typeof a === 'string' && typeof b === 'string') {

return a.concat(b);

}

throw new Error('Invalid arguments. Both arguments must be either numbers or strings.');

}

instanceof

class Customer { isCreditAllowed(): boolean { // ... return true; } } class Supplier { isInShortList(): boolean { // ... return true; } } type BusinessPartner = Customer | Supplier; function signContract(partner: BusinessPartner) : string { let message: string; if (partner instanceof Customer) { message = partner.isCreditAllowed() ? 'Sign a new contract with the customer' : 'Credit issue'; } if (partner instanceof Supplier) { message = partner.isInShortList() ? 'Sign a new contract the supplier' : 'Need to evaluate further'; } return message; }in

The

inoperator carries a safe check for the existence of a property on an object. You can also use it as a type guard.function signContract(partner: BusinessPartner) : string { let message: string; if ('isCreditAllowed' in partner) { message = partner.isCreditAllowed() ? 'Sign a new contract with the customer' : 'Credit issue'; } else { // must be Supplier message = partner.isInShortList() ? 'Sign a new contract the supplier ' : 'Need to evaluate further'; } return message; }User-Defined Type Guard

User-defined type guards allow you to define a type guard or help TypeScript infer a type when you use a function.

A user-defined type guard function is a function that simply returns

arg is aType. For example:function isCustomer(partner: any): partner is Customer { return partner instanceof Customer; }In this example, the

isCustomer()is a user-defined type guard function. Now you can use it in as follows:function signContract(partner: BusinessPartner): string { let message: string; if (isCustomer(partner)) { message = partner.isCreditAllowed() ? 'Sign a new contract with the customer' : 'Credit issue'; } else { message = partner.isInShortList() ? 'Sign a new contract with the supplier' : 'Need to evaluate further'; } return message; }

Type Casting

Type casting allow you to convert a variable from one type to another type.

In TypeScript, you can use the as keyword or <> operator for type castings.

- Type Casting using the

askeyword

The following selects the first input element by using the querySelector() method:

let input = document.querySelector('input["type="text"]');

Since the returned type of the document.querySelector() method is the Element type, the following code causes a compiler error:

console.log(input.value);JS

The reason is that the value property doesn’t exist in the Element type. It only exists on the HTMLInputElement type.

To resolve this, you can use type casting that cast the Element to HTMLInputElement by using the as keyword like this:

let input = document.querySelector('input[type="text"]') as HTMLInputElement;

Now, the input variable has the type HTMLInputElement.

Another way to cast the Element to HTMLInputElement is when you access the property as follows:

let enteredText = (input as HTMLInputElement).value;

Note that the HTMLInputElement type extends the HTMLElement type that extends to the Element type. When you cast the HTMLElement to HTMLInputElement, this type casting is also known as a down casting.

The syntax for converting a variable from typeA to typeB is as follows:

let a: typeA;

let b = a as typeB;

Code language: TypeScript (typescript)

- Type Casting using the <> operator

Besides the as keyword, you can use the <> operator to carry a type casting. For example:

let input = <HTMLInputElement>document.querySelector('input[type="text"]');

console.log(input.value);

The syntax for type casting using the <> is:

let a: typeA;

let b = <typeB>a;

Type Assertion

Type assertions instruct the TypeScript compiler to treat a value as a specified type. It uses the as keyword to do so:

expression as targetType

A type assertion is also known as type narrowing. It allows you to narrow a type from a union type.

Note that a type assertion does not carry any type casting. It only tells the compiler which type it should apply to a value for the type checking purposes.

You can also uses the angle bracket syntax <> to assert a type, like this:

<targetType> value

For example:

let netPrice = <number>getNetPrice(100, 0.05, false);

Note that you cannot use angle bracket syntax <> with some libraries such as React.

Intersection Type

An intersection type creates a new type by combining multiple existing types. The new type has all features of the existing types.

To combine types, you use the & operator as follows:

type typeAB = typeA & typeB;

The typeAB will have all properties from both typeA and typeB.

interface BusinessPartner {

name: string;

credit: number;

}

interface Identity {

id: number;

name: string;

}

interface Contact {

email: string;

phone: string;

}

type Employee = Identity & Contact;

type Customer = BusinessPartner & Contact;

type Employee = Identity & Contact;

let e: Employee = {

id: 100,

name: 'John Doe',

email: 'john.doe@example.com',

phone: '(408)-897-5684'

};

When you intersect types, the order of the types doesn’t matter.

Function

Optional Parameters

Because the compiler thoroughly checks the passing arguments, you need to annotate optional parameters to instruct the compiler not to issue an error when you omit the arguments.

To make a function parameter optional, you use the

?after the parameter name.function multiply(a: number, b: number, c?: number): number { if (typeof c !== 'undefined') { return a * b * c; } return a * b; }The optional parameters must appear after the required parameters in the parameter list.

Default Parameters

function name(parameter1:type=defaultvalue1, parameter2:type=defaultvalue2,...) { // }Notice that you cannot include default parameters in function type definitions. The following code will result in an error:

let promotion: (price: number, discount: number = 0.05) => number; //error TS2371: A parameter initializer is only allowed in a function or constructor implementation.both the default parameters and trailing default parameters share the same type.

function applyDiscount(price: number, discount: number = 0.05): number { // ... } function applyDiscount(price: number, discount?: number): number { // ... } //both are (price: number, discount?: number) => numberHowever, default parameters don’t need to appear after the required parameters.

When a default parameter appears before a required parameter, you need to explicitly pass

undefinedto get the default initialized value.Rest Parameters

To declare a rest parameter, you prefix the parameter name with three dots and use the array type as the type annotation:

function fn(...rest: type[]) { //... }function overloadings

function add(a: number | string, b: number | string): number | string { if (typeof a === 'number' && typeof b === 'number') return a + b; if (typeof a === 'string' && typeof b === 'string') return a + b; }The union type doesn’t express the relationship between the parameter types and results accurately.

To better describe the relationships between the types used by a function, TypeScript supports function overloadings.

function add(a: number, b: number): number; function add(a: string, b: string): string; function add(a: any, b: any): any { return a + b; } //with optional parameter function sum(a: number, b: number): number; function sum(a: number, b: number, c: number): number; function sum(a: number, b: number, c?: number): number { if (c) return a + b + c; return a + b; }

Class

JavaScript does not have a concept of class like other programming languages such as Java and C#. In ES5, you can use a constructor function and prototype inheritance to create a “class”.

function Person(ssn, firstName, lastName) {

this.ssn = ssn;

this.firstName = firstName;

this.lastName = lastName;

}

Person.prototype.getFullName = function () {

return `${this.firstName} ${this.lastName}`;

}

let person = new Person('171-28-0926','John','Doe');

console.log(person.getFullName());

ES6 allowed you to define a class which is simply syntactic sugar for creating constructor function and prototypal inheritance

class Person {

ssn;

firstName;

lastName;

constructor(ssn, firstName, lastName) {

this.ssn = ssn;

this.firstName = firstName;

this.lastName = lastName;

}

getFullName() {

return `${this.firstName} ${this.lastName}`;

}

}

TypeScript class adds type annotations to the properties and methods of the class. The following shows the Person class in TypeScript:

class Person {

ssn: string;

firstName: string;

lastName: string;

constructor(ssn: string, firstName: string, lastName: string) {

this.ssn = ssn;

this.firstName = firstName;

this.lastName = lastName;

}

getFullName(): string {

return `${this.firstName} ${this.lastName}`;

}

}

Access Modifier

Access modifiers change the visibility of the properties and methods of a class. TypeScript provides three access modifiers:

private

The

privatemodifier limits the visibility to the same-class only. When you add theprivatemodifier to a property or method, you can access that property or method within the same class. Any attempt to access private properties or methods outside the class will result in an error at compile time.class Person { private ssn: string; private firstName: string; private lastName: string; // ... }protected

The

protectedmodifier allows properties and methods of a class to be accessible within same class and within subclasses.To make the code shorter, TypeScript allows you to both declare properties and initialize them in the constructor like this:

class Person { constructor(protected ssn: string, private firstName: string, private lastName: string) { this.ssn = ssn; this.firstName = firstName; this.lastName = lastName; } getFullName(): string { return `${this.firstName} ${this.lastName}`; } }public

The public modifier allows class properties and methods to be accessible from all locations. If you don’t specify any access modifier for properties and methods, they will take the public modifier by default.

Note that TypeScript controls the access logically during compilation time, not at runtime.

readonly

TypeScript provides the readonly modifier that allows you to mark the properties of a class immutable. The assignment to a readonly property can only occur in one of two places:

- In the property declaration.

- In the constructor of the same class.

class Person {

readonly birthDate: Date;

constructor(birthDate: Date) {

this.birthDate = birthDate;

}

}

Like other access modifiers, you can consolidate the declaration and initialization of a readonly property in the constructor like this:

class Person {

constructor(readonly birthDate: Date) {

this.birthDate = birthDate;

}

}

Readonly vs. const

The following shows the differences between readonly and const:

readonly | const | |

|---|---|---|

| Use for | Class properties | Variables |

| Initialization | In the declaration or in the constructor of the same class | In the declaration |

Interface

TypeScript interfaces define the contracts within your code. They also provide explicit names for type checking.

By convention, the interface names are in the camel case. They use a single capitalized letter to separate words in there names.

interface Person {

firstName: string;

lastName: string;

}

function getFullName(person: Person) {

return `${person.firstName} ${person.lastName}`;

}

let john = {

firstName: 'John',

lastName: 'Doe'

};

console.log(getFullName(john));

Optional Properties

An interface may have optional properties. To declare an optional property, you use the question mark (?) at the end of the property name in the declaration

interface Person {

firstName: string;

middleName?: string;

lastName: string;

}

Function Types

In addition to describing an object with properties, interfaces also allow you to describe function types.

To describe a function type, you assign the interface to the function signature that contains the parameter list with types and returned types.

interface StringFormat {

(str: string, isUpper: boolean): string

}

Class Types

The interface can also be used to define a contract between unrelated classes.

For example, the following Json interface can be implemented by any unrelated classes:

interface Json {

toJSON(): string

}

The following declares a class that implements the Json interface:

class Person implements Json {

constructor(private firstName: string,

private lastName: string) {

}

toJson(): string {

return JSON.stringify(this);

}

}

extending

interface Mailable {

send(email: string): boolean

queue(email: string): boolean

}

interface FutureMailable extends Mailable {

later(email: string, after: number): boolean

}

Like classes, the FutureMailable interface inherits the send() and queue() methods from the Mailable interface.

An interface can extend multiple interfaces, creating a combination of all the interfaces.

interface A {

a(): void

}

interface B extends A {

b(): void

}

interface C {

c(): void

}

interface D extends B, C {

d(): void

}

TypeScript allows an interface to extend a class. In this case, the interface inherits the properties and methods of the class. Also, the interface can inherit the private and protected members of the class, not just the public members.

It means that when an interface extends a class with private or protected members, the interface can only be implemented by that class or subclasses of that class from which the interface extends.

By doing this, you restrict the usage of the interface to only class or subclasses of the class from which the interface extends. If you attempt to implement the interface from a class that is not a subclass of the class that the interface inherited, you’ll get an error. For example:

class Control {

private state: boolean;

}

interface StatefulControl extends Control {

enable(): void

}

class Button extends Control implements StatefulControl {

enable() { }

}

class TextBox extends Control implements StatefulControl {

enable() { }

}

class Label extends Control { }

// Error: cannot implement

class Chart implements StatefulControl {

enable() { }

}

Generics

TypeScript generics allow you to write the reusable and generalized form of functions, classes, and interfaces.

In order to avoid code duplication. We can:

function getRandomAnyElement(items: any[]): any {

let randomIndex = Math.floor(Math.random() * items.length);

return items[randomIndex];

}

This solution works fine. However, it has a drawback.

It doesn’t allow you to enforce the type of the returned element. In other words, it isn’t type-safe.

A better solution to avoid code duplication while preserving the type is to use generics.

The following shows a generic function that returns the random element from an array of type T:

function getRandomElement<T>(items: T[]): T {

let randomIndex = Math.floor(Math.random() * items.length);

return items[randomIndex];

}

function merge<U, V>(obj1: U, obj2: V) {

return {

...obj1,

...obj2

};

}

This function uses type variable T. The T allows you to capture the type that is provided at the time of calling the function.

This getRandomElement() function is generic because it can work with any data type including string, number, objects,…

By convention, we use the letter T as the type variable. However, you can freely use other letters such as A, B C, …

The following shows how to use the getRandomElement() with an array of numbers:

let numbers = [1, 5, 7, 4, 2, 9];

let randomEle = getRandomElement<number>(numbers);

console.log(randomEle);

This example explicitly passes number as the T type into the getRandomElement() function.

In practice, you’ll use type inference for the argument. It means that you let the TypeScript compiler set the value of T automatically based on the type of argument that you pass into, like this:

let numbers = [1, 5, 7, 4, 2, 9];

let randomEle = getRandomElement(numbers);

console.log(randomEle);

In this example, we didn’t pass the number type to the getRandomElement() explicitly. The compiler just looks at the argument and sets T to its type.

Generics Constraint

In order to denote the constraint, you use the extends keyword. For example:

function merge<U extends object, V extends object>(obj1: U, obj2: V) {

return {

...obj1,

...obj2

};

}

Because the merge() function is now constrained, it will no longer work with all types. Instead, it works with the object type only.

function prop<T, K>(obj: T, key: K) {

return obj[key];

}

//Type 'K' cannot be used to index type 'T'.

function prop<T, K extends keyof T>(obj: T, key: K) {

return obj[key];

}

- Use

extendskeyword to constrain the type parameter to a specific type. - Use

extends keyofto constrain a type that is the property of another object.

Generics Class

A generic class has a generic type parameter list in an angle brackets <> that follows the name of the class:

class className<T>{

//...

}

class className<K,T>{

//...

}

class className<T extends TypeA>{

//...

}

class Stack<T> {

private elements: T[] = [];

constructor(private size: number) {

}

isEmpty(): boolean {

return this.elements.length === 0;

}

isFull(): boolean {

return this.elements.length === this.size;

}

push(element: T): void {

if (this.elements.length === this.size) {

throw new Error('The stack is overflow!');

}

this.elements.push(element);

}

pop(): T {

if (this.elements.length == 0) {

throw new Error('The stack is empty!');

}

return this.elements.pop();

}

}

Generics Interface

Like classes, interfaces also can be generic. A generic interface has generic type parameter list in an angle brackets <> following the name of the interface:

interface interfaceName<T> {

// ...

}

interface interfaceName<U,V> {

// ...

}

interface Pair<K, V> {

key: K;

value: V;

}

interface Options<T> {

[name: string]: T

}

let inputOptions: Options<boolean> = {

'disabled': false,

'visible': true

};